EVP - things you should know

EVP is the ‘electronic voice phenomena’. It consists of apparent voices discovered on sound recordings when none was noticed at the time of the recording. For this reason is commonly considered to be paranormal in origin. However, there are aspects of EVP, to do with how humans understand speech, that are not well-known and raise significant doubts about the existing evidence. This article is a brief introduction to these concerns. For a much more detailed discussion.

The popular idea is that EVP represents voices from spirits, or some other unknown entities. Hence EVP’s other name - ITC: Instrumental TransCommunication. However, before the idea of communication can be accepted, it must first be established that what is being heard is really voices. Despite the wealth of evidence available, on the web for instance, the matter is by no means finalised.

Voices from nowhere

EVP researchers use various different methods to obtain their recordings. Some dedicated researchers, many of whom have been around for decades, don’t use a microphone for their recordings. They may, however, use a white noise generating circuit to obtain source sounds. Other EVP enthusiasts use a microphone in addition to a white noise generator (like tuning a radio between stations). Yet others set up sound recorders in quiet locations to see what they can pick up. In many cases the locations selected are allegedly haunted. Some people have claimed to hear the voices at the time of the recording. The reason these voices are considered paranormal is that the voice did not come from anyone present (though, of course, this doesn’t exclude a voice from somewhere outside the building).

EVP recordings tend to share various characteristics. Firstly, they are usually very short, just one word or short phrase. They also all tend to sound similar to each other, unlike normal human voices where you can recognise individuals by the sound of their voice. The voices can sound often sound oddly ‘electronic’. Thirdly, the rhythm or speed (faster or slower) of the words is often odd compared to how a normal human being would say it. Fourthly, different people may interpret the same EVP recording as completely different words. Indeed, one person may even change their mind about the words they hear on a particular recording if they haven’t heard it for a while. Fifthly, though the apparent words heard in EVP recordings may sometimes appear relevant to the situation (answering a voiced question, for instance) they are often cryptic or quite irrelevant.

There are many natural reasons why a noise may appear on a sound recording even though it wasn’t heard at the time. Sound recorders with a microphone fitted can easily pick up sounds that humans can’t hear if their sensitivity is set high. This can happen without operator intervention, or even knowledge, due to auto gain circuits fitted to most recorders that increase sensitivity automatically when ambient sound levels are low. Directional microphones may also pick up sounds that humans don’t hear if they happened to be pointing towards a faint sound source (equally some sounds may be obvious to the operator but not picked up by the recorder for similar reasons). Even recorders with no microphone fitted may be subject to electromagnetic interference or internal electronic noise.

In addition some sounds, though perfectly audible (and picked up by multiple recorders in the area at once) at the time of recording, may not noticed by operators simply because they didn’t appear to be voices. Such ‘noise’ may only sound more ‘voice-like’ when subject to intense scrutiny later, when the recording is reviewed. Faint sounds, even real voices, may also be missed, at the time of recording, because people get used to background noise levels after a few minutes of exposure (habituation) and subsequently only hear loud things.

Sound recorders can also pick up mechanical sounds that are not heard at the time of recording. These could include tape movements (in analogue recorders), objects brushing against the recorder (or something it is attached to) or the wind or draughts blowing across the microphone. For this reason, people should avoid holding recorders while they are working.

Some EVP researchers argue that if voices are below the frequency range that people can speak, it must indicate a paranormal origin. While it certainly demonstrates that our brains are flexible enough interpret sound as speech sounds outside the normal spoken frequency range, it doesn’t prove a paranormal origin (or even that the sound is speech).

How do we know a noise is human speech?

When you listen to a sound recording, all you hear is the amplitude and frequency of the sound. Unless you recognise what is causing the sound its origin will remain unknown. Given the number of possible natural causes for sounds (not noticed at the time of recording), it is not a reasonable basis on which to call the noises paranormal. Even if such noises sound like voices it might simply be that someone spoke and no one remembered it. No matter how the apparent voices arrive, we end up with a recording. To find out if it is paranormal, we need to determine if that recording really is speech.

EVP recordings are often labeled or introduced, so that listeners know in advance their generally accepted interpretation. Unfortunately, this widely used practice introduces a strong element of psychological suggestion which virtually forces the mind of the listener to ‘hear’ it. When recordings are given to listeners without knowing what to expect, interpretations often vary widely. This is because, in many cases, it is difficult to make out what is being said, if anything. It might be best to play people fairly lengthy recordings, with some EVP in them somewhere, and merely ask people what they think they can hear! They may decide that a section of EVP is just noise. However, even playing such lengthy extracts can have its problems.

Suppose you are played a recording where someone asks a ghost a question. The questioner hears no answer at the time but there is a faint noise found soon after the question on the recording. When listening to the playback, many people will unconsciously turn the noise not simply into a faint voice but also into an apparently appropriate answer! If someone asks ‘is there anyone there’, your brain will immediately start expecting the answer ‘yes’! And yet, someone hearing only the ‘noise’ bit of the recording, with no knowledge of the preceding question, may hear it as ‘deaf’ of ‘bell’ or simply a noise! Even though no one has told the listener what to expect, the question, and they very fact it is asked, have made psychological suggestion a major factor.

Then the central question becomes this - how do we humans decide that a particular sound is human speech? How do we differentiate between the sound of a gate slamming, a piece of music, a static hum and a human voice? Most people would say that it is obvious - we recognise words! Unfortunately, it is all too easy into fooling human brains into hearing ‘voices’ when it is just noise. Telling someone they are about to hear a voice does this rather well!

How we understand speech

The human brain is hard-wired to find combinations of integer harmonic frequencies pleasing (which may explain why we enjoy music). Combined integer harmonic sounds are two or more separate tones, heard at the same time, where their frequencies are related by a simple integer ratio. For instance, the two frequencies 1000 Hz and 2000 Hz heard together would be an combined integer harmonic because 2000 Hz is exactly twice 1000 Hz. Human speech uses such simple harmonic tones to construct the sounds in words. In speech the harmonic ratios are typically numbers like 2/5 , 1/2, 1/3 etc. These tones heard together are called formants. Formants are discrete sounds within a word, equating to phonemes in phonetics. Instead of hearing the two tones combined a single musical note, our brain interprets the sound as a discrete sound within a word instead. So, for instance, the ‘O’ sound might typically consist of a 500 Hz and 1000 Hz frequency combination.

The only information we get from our ears is the amplitude, frequency and time of arrival of sounds. It is left entirely to our brains to interpret what the sounds are, relying mainly on experience, context and expectation. The brain generally interprets sounds in one of three ‘modes’. In one mode it interprets a sound as random noise. In another mode the same sound appears to be music. In the third mode, the same sound becomes speech. Some people, ‘amusical’ individuals, do not enjoy music. They just hear noise. They are, effectively, missing the ‘music mode’.

How does the brain decide how to interpret a sound? It is largely a matter of expectation. If we hear tones from a musical scale, particularly set to a fixed rhythm, we are likely to hear it is as music. If we hear sounds with the typical frequency range and rhythms of speech we will probably try to interpret the sound as words. If we do not hear a sound as music or speech, we will hear it in its raw state, as a mixture of frequencies.

Hearing is not always believing

If we are listening to someone in a noisy situation we may not hear all the words. Our brains will ‘fill in’ the gaps with likely words, sometimes wrong, based on expectation. We will actually hear and remember ‘filled in’ words even if they are wrong. The words we hear are produced in our brains, not our ears.

In the phoneme restoration effect, someone is played a recording of a spoken sentence where one word is replaced by white noise of the same duration. And yet, people still ‘hear’ the missing word. Their brain has inserted it using context and expectation. In the verbal transformation effect, someone is played a word repeatedly. After many repeats, the word turns into another with a similar sound structure (‘truce’ may transform to ‘truth’, for instance). These effects, together with other scientific evidence, demonstrate that the brain decides what it hears based on experience, context and expectation. This explains why EVP recordings, which are often very noisy, can be interpreted differently by different individuals. Your ear hears sounds but only your brain hears words.

Noise that sounds like speech

Almost any simple noise, like white noise, can sound like speech if the person listening to it is in ‘speech mode’. The more voice-like features in the noise (such as frequencies and rhythm), the more people will interpret it as words. If there are peaks in the frequency spectrum of the noise that happen, by chance, to form a harmonic ratio, as in formants, there is a much higher chance it will sound like speech. If there are variations in the overall amplitude of the sound giving a rhythm, similar to words in human speech, that will also greatly increase the chances of its being interpreted as a voice. Also, if the spectrum envelope of the sound (the overall frequency range) is restricted to that typical of a human voice, the illusion of speech is increased. The actual frequencies of the harmonics and the spectrum envelope don’t have to be identical to normal human speech. Research has shown that people still understand speech even when it has been frequency shifted.

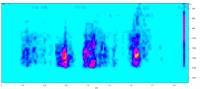

Noise with these sort of characteristics is called ‘formant noise’ and it can sound uncannily like real speech. It can be good enough to trip the brain into ‘speech mode’. Though the apparent formants may make no sense (as they are noise, not words), our brains will work hard to turn the result into recognisable words. That’s because they use a ‘top-down’ process to processing speech, trying to fit likely words to the apparent formants present. It explains why, with formant noise, you never ‘hear’ partial words. The words come from your brain, not the sound, and are made to fit the noise. In the same way, whole phrases can emerge. You may need to listen to formant noise several times to fix the phrase as your brain tries various likely alternatives. If someone tells you beforehand what the ‘words’ are meant to be, you will often hear it straight away. Here is a spectrogram of some formant noise

Formant noise can share known characteristics with typical EVP recordings. For instance, it is often short, one word or short phrase. This is because you need just the the right rhythm in the sound to make it sound like words and such instances are rare. Rhythms that are not quite right may produce another typical aspect of EVP, slow or fast words. Formant noise can also sound ‘electronic’ if a recording has been processed, as is often the case. The lack of individually recognizable voices would be due to the fact that no actual vocal tract is involved in producing the apparent words.

Is EVP paranormal?

The existence of formant noise does not mean EVP is not paranormal. However, it does means that precautions need to be observed when recording, processing and listening to EVP to avoid formant noise. For instance:

Recording EVP

- use a good sound recorder in high quality mode - some EVP recordings have a restricted frequency range due to equipment limitations or using low quality or economy modes

- put the recorder down and don’t touch it or anything in contact with it during recordings - to avoid accidental mechanical noises

- avoid file compressing sound files - compression and use of lossy formats can alter noise

- use two different model recorders together - to avoid internal noise or susceptibilities peculiar to a particular model of recorder

- use multiple sound recorders together at a particular location - this will allow both a chance to locate the source of the sound (through triangulation) and, by comparing recordings, it may be possible to identify what it is (whether voice or not)?*

* Many people who have tried using multiple recorders for EVP have reported that they typically turn up only on one recorder. This has been taken as a sign that the source is paranormal. However, it might also indicate a faint natural sound source near just one recorder, which would also explain why it was not heard at the time of recording!

Processing EVP

- don’t edit or process EVP sound files - noise reduction software accentuates frequency peaks making apparent formants, if present, more prominent and reducing frequency range affects the spectrum envelope

Listening to EVP

- get a third party to judge recordings without telling them it contains apparent voices

- play only ‘answers’ to judges from ‘question and answer’ sessions* to avoid suggestion effects

- don’t put recordings on endless repeat, just play them a standard number of times each

*Some researchers claim that their EVP must be paranormal because the ‘voice’ answers their questions. However, such ‘answers’ often have multiple possible interpretations. Like many EVP messages, such answers tend towards the tangential or even cryptic. This seems odd if they are real communications.

The techniques outlined here should minimise the problems of formant noise though they may not eliminate it entirely. Any apparent voices should also be analysed using techniques like spectrum analysis.

This is just a brief introduction to the topic of formant noise. You can read about analysing EVP here and hear demonstrations of formant noise and other effects here.

Hearing formant noise directly

As formant noise comes from ambient noise sources, it may not always require a sound recorder to hear it. Some rotary electrical equipment, like fans, can produce voice-like sounds on occasion. This is particularly noticeable if the fan does not run smoothly or if there is a second (non-voice) noise in addition. This could explain some ghostly voices or whispering heard in haunting cases.

Author :© Maurice Townsend 2009, 2011

Other ASSAP Articles

Unmatched Value, Unfinished Evolution: Why ASSAP Is Reviewing Membership for 2026

REVIEW: Even More…Ghost Stories by Candlelight at Shakespeare North Playhouse by Rob Gandy

Dark Secrets The Exhibition delights in darkness!

Previewing the Dark Secrets Exhibition!

ASSAP Announces Formation of Expert Advisory Panel

Exceptional Training Weekend - is available to book! Find out more!