Paranormal witness memory

Witness testimony is central to establishing the facts of paranormal case. It is often the only access we have to unexplained events. We know that witnesses can be fooled by misperception and hallucination but, once they've experienced something, how reliable is their memory?

Computer memory is extremely reliable. As well as using tried, stable technologies it usually includes mechanisms to verify that what is stored is correct. Human memory, by comparison, is fallible, fades with time and there is often no way to verify it. And yet, we use it in court cases and sometimes for scientific observation.

Psychological suggestion and priming

Scientific experiments have shown that what we recall about a situation can be affected by being primed in advance. If people are shown a random list of words, including some like 'bed' and 'doze', and are later asked if the word 'sleep' appeared in the list, they will often say yes, even when it didn't. This is priming or psychological suggestion - putting an idea in your head that then affects subsequent perception and memory.

If you attend a ghost vigil and see a shadow resembling a figure, you are more likely to interpret it as a ghost than if you just visited at the same time of day as a tourist or guest. On a vigil you are effectively primed with the idea that you are at a haunted location. If you strongly believe or disbelieve in the paranormal, that too will increase or decrease your chances of interpreting something as paranormal in any situation, not just vigils. We are usually not consciously aware of priming or suggestion.

Tidy minds

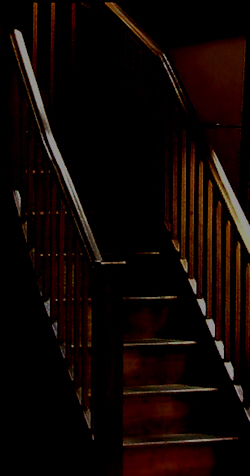

An example of such an ambiguous stimulus is the photo (right) that is clearly a shadow but it is also 'human' shaped. If briefly glimpsed on a vigil, some people may say this shadow is a ghost. As a result, our brain may 'edit' what we see to conform with the idea that it is a ghost. As this sensory information has been altered before we are even aware of it, it is accepted as true ('seeing is believing'). Similarly, when people hallucinate, this too is accepted consciously as a true perception.

Whether the sensory information we remember is accurate or not, it is still not safe from alteration even when it has been stored in our memories. Our brains may alter our memories, when they are recalled, if they don't 'make sense' in the light of new, conflicting information. These alterations are similarly accepted as true and become part of the long term memory. This process is called confabulation (or false memory).

Confabulation

Confabulation alters existing details of memories, as well as adding new 'events' that never happened. The process happens unconsciously before we are even aware of recalling the memory. Effectively, the brain has decided, without our conscious knowledge, what is true and what isn't, just like in misperception. This memory editing process may also be biased by priming or suggestion.

Confabulation tends to occur when conflicts arise between the existing memory and current information or if memories are examined for detail that they do not contain. If we confer with other witnesses to the same incident, for instance, we might 'alter' our memories to conform with theirs (or the other way round). Changes can also occur when discussing the memory with people who were not fellow witnesses. If asked 'what colour was the ghost's hat?', we might reply 'blue', even it didn't have a hat! Even reading about, or otherwise researching, other people's similar experiences may alter our own.

ASSAP's Phil Walton demonstrated confabulation with his research on witness testimony. People witnessed a staged incident and were asked, directly afterwards, questions about what they'd seen. When asked what rings someone was wearing and on what hand, several people offered answers of 'left', 'right', 'gold' and 'silver' and so on. The person concerned wore no rings! Forced to remember details that didn't exist in their memories, people confabulated.

Confabulation is not lying. Lying is a conscious activity where the person involved is aware that what they are saying is not accurate. When people confabulate, they cannot tell the difference between accurately recalled memories and imaginary additions or alterations. ASSAP has come across very few cases where witnesses have consciously lied over the years. In the vast majority of cases where witness testimony is contradicted by other evidence, it is likely to be confabulation.

It was once thought that confabulation was a symptom of a medical condition, like dementia or amnesia. However, research has revealed that we all do it to some extent. Our brains always want our memories to 'make sense', even if it means altering them and not telling us!

Memory fragments

We only remember a fraction of what we experience. We may only remember fragments of a particular event and those bits may not even be the most important. We might remember what someone was wearing, for instance, but not their name!

While there are useful techniques for recovering memory, by pressing for too many details we may simply encourage people to confabulate. The problem is, these confabulated details will form part of the witness evidence in paranormal cases. This could cause problems when we are trying to explain the reported event. We may be trying to explain some details that never even happened!

Judging how good a recollection is

Some people are better at remembering than others. An interesting way to test someone's memory is to get them to imagine a scene in the future. If they are able to describe it in detail, their memory is good. If they cannot form a strong mental picture of an imaginary future scenario, their memory is not so good. We use the same brain mechanisms to remember the past as we do to imagine the future, which is why the test works. It might be worth trying this test with people you interview. Of course, the fact that someone has a good memory doesn't necessarily mean their memory hasn't been altered.

How do you know if someone's memory has been significantly altered by confabulation? One method is a site examination of the place where an apparent paranormal experience took place. You can check all the details the witness reported against what you find on site to see if there any major conflicts. You may find obvious things that the witness ought to have noticed, but didn't or did notice but aren't present. You might also discover that, due to the geometry of the site, the scene could not have looked as they described. All such discrepancies may indicate that memories have altered since the event. Of course, this test won't work if the witness has visited the scene since the experience.

Fading memories

Memories fade with time or, to be more precise, with neglect. If we continually recall something it will remain fresh and doesn't fade. However, things we haven't recalled for years will fade and ultimately vanish. This seems to be a deliberate brain mechanism designed to keep our memories a manageable size.

Some memories are formed more strongly than others. Those associated with emotions tend to be stronger. We also form stronger memories when we pay attention, or concentrate, at the time. So, if seeing a ghost has a strong emotional effect on a witness, it is likely to be stored well. If, however, someone only realises they have seen a ghost after the event (when they find they were alone in a locked building, for instance) the memory may be weaker and details not stored so well.

Stress and the xenonormal

Interestingly, when people experience uncertainty or the unfamiliar (as in the xenonormal), they often secrete a stress hormone called cortisol. This hormone affects their memory of the event, sometimes making it vivid ('flash-bulb memory'), though not necessarily accurate, and biasing it towards negative feelings. Certainly, many people find encounters with the xenonormal disturbing and do not want to repeat the experience. This is typical of the effect of cortisol. Research shows that, although flashbulb memories are vivid and detailed, they are not particularly accurate and alter with time like other memories.

Actual fear can partially or totally wipe the memory of an incident. So if a witness is distressed by what they experience, their memory of it may be particularly vague and unreliable. They may confabulate to fill in the obvious gaps in their recall.

Changing witness stories

Sometimes, when you investigate a case, an obvious xenonormal solution will occur to you that fits the description given by the witness very well. However, when you put this idea to the witness they will suddenly 'remember' other points about their observation that (a) they never mentioned before, in spite of rigorous interviewing, and (b) tend to confirm the paranormal interpretation that the witness already places on what they saw.

While it is entirely possible that the witness may remember more things over time, another possibility is confabulation. If the witness is convinced that they've seen a ghost they may, quite unconsciously, add further 'memories' to 'plug the gap' that might otherwise allow a xenonormal explanation.

Some witnesses gratefully accept the suggested xenonormal explanation as they simply want a satisfying solution. But those who may have profoundly convinced themselves that they've experienced something extraordinary may be reluctant to let that idea go and so, unconsciously, confabulate. Given that (a) most cases do end with xenonormal explanations and (b) the fact that this scenario happens frequently, it tends to support the idea that confabulation is indeed taking place. Obviously, no investigator can assume such a thing but if it happens repeatedly, with several xenonormal suggestions producing more and more 'new memories', it has to considered a strong possibility.

Conclusions

The sooner you interview a witness after an apparent paranormal experience the better. Not only do memories fade with time but, more seriously, they can be altered through recall and discussions with other people. The best you can expect is to extract fragments of the experience.

Here are a few general guidelines for interviews to avoid confabulation:

- avoid questions that force recollection of unreasonable levels of detail

- avoid questions that force 'either/or' decisions ('open' rather than 'closed' questions)

- use 'free recall' methods (where the witness recalls freely without interruption) to get the basic facts

- try to gauge the emotional impact, at the time, of the experience

- adopt a neutral attitude to avoid suggestion or priming

- find out how much the witness has discussed their experience with others (particularly those with strong beliefs concerning the experiences) or knows about similar events from prior knowledge or subsequent research

- ask what the witness believes their experience represents and their attitude to the paranormal

- ask the witness to imagine a future event to see how strong a mental picture they form

Given the problems with misperception and confabulation, we should not rely too much on any single witness's testimony. If we want to establish whether there is a haunting is worth investigating, we need to find two or more independent witnesses (ie. not aware of each other's accounts) to see if they agree on important points.

PS: Memory, visual images and stories

There are memory competitions where people have to remember the sequence of cards in a randomly shuffled playing card deck. It sounds astonishing but people recall the sequence of entire decks after studying them for a few minutes. How do they accomplish such astonishing feats of memory?

A common way is the method of loci. Every playing card is associated mentally with a particular place and the sequence strung together as an imaginary journey. What is interesting is that a whole image, containing a lot of information, is used to recall a playing card which can be defined with just two items - suit and rank. So an awful lot of superfluous information is being stored just to recall something simple. Also interesting is that it is specifically visual images that are used to 'tag' memories.

This clearly relates to the way our memory works and it might explain confabulation and the way witness accounts become exaggerated over time. If a witness saw a distant dark figure on a dark night, there isn't much detail to recall. However, if the witness interpreted the figure as a ghost, straight away there is a 'story' attached to the sighting (and maybe even a particular visual image) that makes it more memorable. When asked to describe the figure, the witness may confabulate details that 'confirm' that the figure was a ghost, such as it was wearing period costume, when in reality no clothing was visible.

This could explain how our cultural ideas of ghosts, and other anomalies, can feed directly into witness accounts. It may also explain why real life ghost accounts are much less dramatic and unambiguously weird than 'traditional' accounts. If you can get to a witness soon after their experience, and question them carefully, you may find out what they really saw, as opposed to what they might have confabulated after many retellings.

Author :© Maurice Townsend 2009, 2010

Other ASSAP Articles

Unmatched Value, Unfinished Evolution: Why ASSAP Is Reviewing Membership for 2026

REVIEW: Even More…Ghost Stories by Candlelight at Shakespeare North Playhouse by Rob Gandy

Dark Secrets The Exhibition delights in darkness!

Previewing the Dark Secrets Exhibition!

ASSAP Announces Formation of Expert Advisory Panel

Exceptional Training Weekend - is available to book! Find out more!