Hypnotic regression case study

CERDIC THE SAXON - A LIFE

Hypnosis is currently a controversial subject. Techniques that claim to recover early life memories are being heavily criticised. In its early days ASSAP conducted a careful investigation into the subject with surprising results.

Introduction

The hypnotist glanced around the darkened room quickly. His gaze then returned to the small table by his side containing notes and writing-pad. The table was illuminated by a dim, shaded reading lamp. All was well. He leaned towards the dark, indistinct human form huddled on the bed before him. Don Brown was breathing slowly and deeply. He had now entered one of the deepest states of trance. They had already been through the usual process of age regression, and several dramatic incidents from the man’s childhood years were recorded on tape.

Now came the big step backwards. The hypnotist licked his lips in apprehension and took a deep breath. ‘So far, Don, we have enjoyed these journeys through time, and now we shall walk together along an even more interesting road. Back, back, even further in time. Before and beyond the time you were born into this life ... ‘The hypnotist’s voice was soft, reassuring and persuasive. ‘You will be at one with the enveloping darkness, and enjoy being so. You will always be comfortable; not too hot, not too cold. And at all times you will hear only my voice.’

He spoke more softly, more slowly. ‘You are floating easily and effortlessly through the darkness ... back, back through the years ... before you were born ... long, long ago ... drifting through time.’ The hypnotist looked quickly at his notes. ‘The year is 1033. It is ten thirty three. January the 18th, 1033 ... you can still hear me ... ‘ He paused. ‘Now who are you?... Tell me your nam ...

‘There was no response. The hypnotist tried again. ‘18th of January 1033 ... your name ... don’t be afraid… tell me your name… ‘ The figure on the bed stirred. The hypnotist’s heart palpitated. ‘Your name .... ‘, he repeated patiently and welcomingly, ‘Who are you?’

‘Cerdic ... ‘, a voice replied uncertainly. It seemed to be struggling to remember. ‘My name is Cerdic. Cerdic of Wrotham.’

Reincarnation

Belief in reincarnation is as old as belief itself. The idea that the essence or soul of a person inhabits a succession of physical bodies was prevalent in most primitive and ancient civilisations; from Australia and China to Alaska, from Persia, Egypt and Greece to the Jews, Incas and Aztecs. It is a philosophy encompassed by most great religions, including Hinduism, Judaism, Taoism and Buddhism. Indeed early Christians were not averse to its philosophy, but after a Council of Constantinople edict in 543 AD it was almost universally rejected by the western Church for the next thousand years. But since the seventeenth century the idea has been embraced and developed by several influential Christian thinkers.

In ancient days it was thought that people reincarnated in various animal forms according to the local mythology, but over the aeons the concept of karma evolved. This suggested that a person needed several lives to gain wide experience as a male or female, rich or poor, good or bad, to compensate and atone for earlier blemishes, and to progress along the path to spiritual perfection. Certainly the philosophy of reincarnation is an appealing one: lives cut short or tragically unfulfilled can be continued, and this instils a feeling of natural justice and fair-play. There are several excellent books dealing with the history and range of ideas encompassed so we need not discuss them in detail here.

My involvement began not with any especial interest in reincarnation, but with hypnosis and its effects. For nearly 25 years I had studied and practised hypnosis, being considerably involved in the regression phenomenon during the burst of activity and plethora of books that came about in the 1970s.

I worked closely with the regressive hypnotist David Lowe, assisting, correlating, travelling throughout Britain researching and uncovering information on peoples’ apparent past lives, evidence for which had previously been provided by one of Mr Lowe’s particularly gifted subjects in deep trance. Although a very open-minded person, David Lowe had been persuaded that the enormous weight of repeated evidence - subject after subject, life after life - pointed only to one explanation - the tapping into memories of previous lives. I was less sure: there were other possibilities, all pretty exotic maybe, but they did need to be tested more fully.

Leaving aside the possibility of fraud and fantasy, there is considerable evidence to suggest that much of the information ascribed to previous lives is due to ‘hidden memory’. Just about everything we see, hear and experience is stored deep in the recesses of the unconscious mind, and can be retrieved in a coherent form as and when the mind decides, even though we may have forgotten this material consciously.

The idea of ancestral memories has been put forward to account for ‘past life characters’, together with the possibility that we might be communicating with the surviving spirits of once-mortal people. Interestingly, another idea prevalent in various Eastern philosophies is that of the Akashic Record. Everything about a person’s life is held in store to be learned from, so the tapping into this databank - if it exists - has to be a possibility.

Hypnosis

What is hypnosis? Although libraries have been written on it, still no-one can define the condition with certainty. The word derives from the Greek ‘hypnos’ meaning ‘sleep’, since the behaviour of many hypnotised people in the 18th and 19th centuries resembled that of somnambulists. This was however just a passing fad, and hypnotic trance is anything but sleep-like. Many say that the mind appears in fact to be in a ‘super-conscious’ mode. Hypnosis is certainly the induction in a person of a state of heightened suggestibility, which can lead to certain mental, and possibly physical, effects.

There is, however, a parallel between hypnosis and sleep. What seems to be going on can best be described as follows - and this is just a simple model for illustrative purposes. When someone is on the point of going to sleep, the body is very relaxed, the eyes are closed, the environment is quiet, and in general outside stimuli and influences disappear. The mind then slowly begins to notice the images and ideas that start to drift upwards from the subconscious or unconscious mind (for present purposes the two terms can be equated). These images soon capture the whole of the attention and become dreams.

In hypnosis complete bodily relaxation has been achieved. The eyes are closed, but this is not always necessary. More important is that by suggestion the operator has focussed the subject’s mind into a form of concentrated attention, thereby ignoring external sights and sounds. And instead of the random images from the unconscious levels, the mind homes in on those generated or suggested by the operator.

Another fallacy still prevalent is that in hypnosis one’s will is surrendered to another. Not at all. We are always at pains to stress that with almost no exceptions, people cannot be made to do or say anything they would not do in appropriate circumstances in the ordinary waking state.

One may point to the apparently incongruous sight of a respected senior businessman woofing on hands and knees in a stage demonstration, but this very same man might regularly be the life and soul of his grandchildren’s Christmas parties. The behaviour has not changed, only the surroundings. There is a great deal of evidence to suggest that the best hypnotic subjects are those who can relax easily and have active imaginations, since they respond best to suggestions made by the operator.

According to the literature most people are capable of being hypnotised to some extent, a small proportion slightly or not at all, and an equally small proportion (around 5%) can enter a deep trance state with the minimum of encouragement. Just as a normal distribution curve in statistics relates to any talent or ability, most of us are somewhere in the middle of the range when it comes to hypnotic susceptibility.

I shall not describe the procedures we used to induce hypnosis as these should not be undertaken by untrained people. There are possibly thousands of different methods but all can be sorted into three broad families, ie. many variants on a few main themes. We used a wide variety, but all of them are based upon the simple concept of the total relaxation of body and mind.

I devised an immensely powerful one we called the ‘Velvet Hammer’, which could almost guarantee to get most people into deep trance within 15 minutes or so. Highly dramatic though this and its effects were, we found that we had better long-term results by a slower, more pedantic ‘bread and butter’ approach. Six or seven training sessions were usually sufficient to enable an average subject to obtain deep trance.

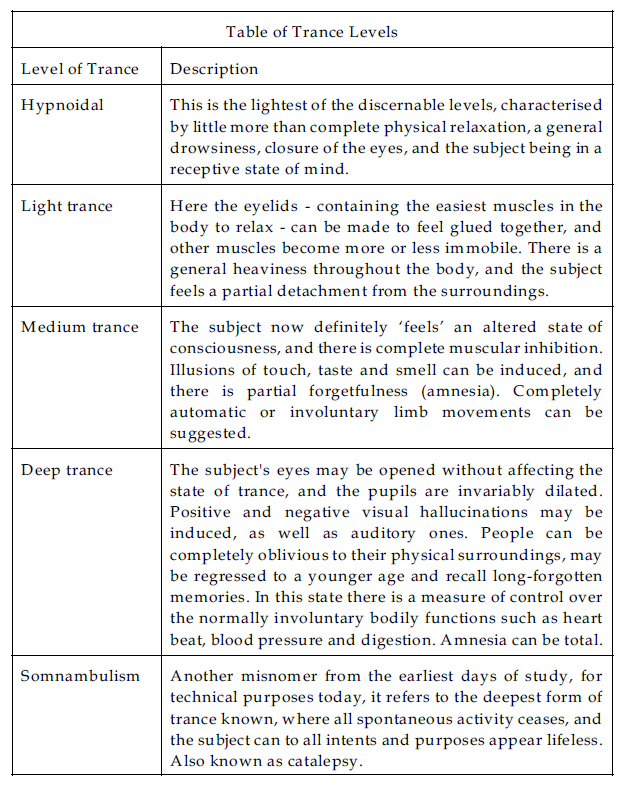

A state of consciousness observably different from the normal waking state, and accompanied by a condition of physical and mental relaxation, is commonly referred to as ‘trance’. While this word can imply all sorts of dubious and dramatic ideas, we shall use it here as a convenient shorthand notation to refer to the altered state of consciousness prevalent in the state of hypnosis. Conventionally, the levels of trance are labelled as follows: hypnoidal, light trance, medium trance, deep trance and somnambulism (see Table of Trance Levels).

There is however no sharp demarcation between these various stages - each merges into the other - so the names employed are broad indications only. Suffice to say that there is little point in trying regression work unless deep trance level is attained, since only here can we guarantee total exclusion of outside influences.

The Protocol

The opportunity for more detailed research came in 1984 when ASSAP was boosting its research programme. After consulting several colleagues - regressive hypnotists I have worked with or alongside, I drafted the project protocol, a thick document which defined the aims of the project and how they would be achieved. In summary the idea was:

- To identify the many factors which may cause the appearance of past lives, enhance their occurrence or influence their content. These could include the belief systems and psychological make-ups of bot hypnotists and subjects, together with an assessment of personality variables, past history and experience, cultural elements, and so on.

- To vary each factor in turn during a series of experiments carried out by hypnotists, psychologists and subjects in different groups. Then to check the verbal material obtained for historical accuracy.

- To analyse the results of these experiments and assess them for significance in terms of a range of theories or models. And if the evidence supported none of the ideas on our list, then we would have to formulate something better.

Some of the questions we wanted answers to were these:

- Is there any similarity between the personalities of successful pairs of hypnotists and subjects? Does a subject with a particular type of character perform better?

- Do hypnotists’ beliefs influence the production of evidence to fit a particular theory?

- How does performance vary with tiredness, illness, etc.?

- Is there any correlation between the personality elements of past life characters of the same subject, and also with their present existence? If past-life experiences are indeed related to memory, might we expect that recent ‘lives’ will be fuller or better-remembered than older ones?

- What sort of information would we obtain if we took people forward in time?

- Are there significant differences in the past-life experiences of people from different nationalities or cultural backgrounds?

If during the course of our researches so far, we did not find complete answers to our queries, the work continues, and we live in hope. But much of value has already emerged, and while most is beyond the scope of this article, some factors impinge directly, and I comment on them in context.

Organisation and Method

Experiments commenced late in 1984 and activity was centred on one group (sometimes two) meeting every Thursday evening in south-east London. Each group had a core membership of about half-a-dozen regulars, but this could swell as commitments of others permitted them to attend. All were members of the Association, but outside observers came along from time to time by invitation. People who formed the team were those who had previously expressed an interest in the subject: most were from London, but one very keen person travelled regularly from deepest Kent. It is important to note that none had strong views for or against the existence of past lives.

Organisation was very democratic: members took turns to act as operators (where fully trained and competent), subjects or monitors. Monitors or ‘scribes’ were essential in our work. All of the sessions were recorded on tape but the brief contents of each were summarised on one page of a standard report form. This enabled us to compile a comprehensive index of past work and also helped plan future meetings more usefully.

Research evenings were conducted with a good-natured, but fairly ruthless discipline. Members started to congregate at 7pm for a prompt start at 7.30. The first session concluded no later than 8.45 and was followed by a short break for tea or coffee. Part Two finished rarely later than 10pm, as the meeting was then adjourned to a nearby pub, where discussion continued in a more convivial environment. This was an essential part of the proceedings which contributed significantly to the cohesiveness of the group. Often there were enough members to have two parallel meetings at the same premises - giving four sessions that night in all.

Communication between the operator and other members of the team was encouraged if new thoughts or ideas emerged during the session, but this was without exception by written note to avoid any sensory clues being passed to the subject.

We generally use the term ‘operator’ instead of ‘hypnotist’ so as to demystify the process. Many people still regard hypnosis with Svengalian suspicion. Yet most persons with common sense who have read widely and practised under supervision can become competent. Initially I was the sole (competent) operator, but it helped enormously when Tom Smith, another highly practised hypnotist, took over one group for a couple of months. Over the course of the following two years most of the core team were trained to a high standard of competence. No small part of the apprenticeship concerned how to deal with the emergencies that can sometimes arise. To know what to do if a deep-trance subject fails to respond to stimuli, or even ‘dies’, was all part of the basic training.

Subject Selection and Training

Before the project commenced, we wondered how we might obtain good deep-trance subjects. Advertise? This might certainly attract many candidates, but from experience I felt most of these would attend to have personal convictions of past lives confirmed. Having met so many people who claimed to have been temple priestesses in ancient Egypt, I often wondered where they housed them all! Seriously, we did realise there were drawbacks with unknown participants, not least the probable high level of fantasy likely to emerge. All members of our team had known each other for some years, which had many advantages, so in the end we decided to train our own subjects!

In a typical session the period of hypnosis usually occupied 30 to 50 minutes; anything longer than this tended to tire subjects. With someone new, most if not all of the time would be taken up with induction processes, especially the trance-deepening exercises. Later however, deep-trance could be induced very quickly, and with safeguards, even by merely mentioning a special code-word.

Utterly essential before bringing the subject back to the normal waking state was a process of desensitisation. Previous personal experience as well as cases reported in the literature deemed it essential to suggest - and get the subjects to agree - that they will be able to remember everything they encountered with vivid clarity, but they would bring back to the waking state no unpleasant influences of a mental, physical or emotional nature whatsoever.

Feedback

We always followed the period of hypnosis by an opportunity for feedback of impressions and observations from the subject, together with questions and discussion. First the subject was invited to run through his or her experience, adding to or amplifying what took place. Invariably the comment came: ‘What I was really trying to say was .... ‘. Then the operator (strictly, always in charge) invited each of the observers in turn to ask questions or make observations and comments. Especially important were subjects’ feelings when something particular happened. The discussion also helped subjects to integrate their experiences with everyday reality, and so avoid certain complications that might otherwise arise.

In deep hypnosis the muscles of the body are so completely relaxed that every syllable uttered is a supreme effort. Information given is necessarily brief and clipped, and the later discussion compensates for this, adding depth and colour. One associated problem is that deep-trance subjects speak so softly that they cannot easily be heard by all observers in the room. We solved this technical difficulty by using a stereo microphone, which as well as being able to pick up voices all around the room with clarity, could in session be suspended close to the subject’s mouth. The input was then amplified through hi-fi speakers.

In early stages we experimented with the ‘closed book’ method. Good deep-trance subjects can be invited to forget all they have experienced in a session, the idea being that if they could not remember, they would be unlikely to go researching facts to corroborate their experiences afterwards. Later we held this idea fallacious: since the hypnotic experience took place at the mind’s unconscious level, any desire to check further might be carried out equally unconsciously. In other words if subjects wanted to check anything they would do so, come what may. We felt we gained considerably more on balance from having the opportunity for discussion after each session.

Regression

When a subject was capable of deep trance it was usual to attempt normal age regression, taking them back to ages of 12, 9, 6, or ... sometimes much earlier. Not even with our most imaginative subjects did we record any instances reported by other workers where they recalled their moment of birth. Very dramatic however were the occasions when a person would sit up from the bed, completely oblivious to the observers and the actual surroundings. Rather, they were in some childhood environment, pointing out the various features to the operator.

In such deep-trance conditions it was easy for an operator to make the subject see people or objects that were not there physically, and indeed make them not see ones that were. It was then but a short step to attempt exploring the ‘past life’ experience.

The usual method was to engage deep-trance subjects in a particular exercise of guided visual imagery. During this they were taken into a special library, and here, as throughout the entire exercise, the subconscious equivalent of their five senses were entirely occupied. Finally, they were invited to take a specific book from a shelf. It had their name on the spine, and after a special descriptive build-up, they were allowed to open it quickly, and read out their first impressions of the summary of chapters on the first page. They were told that these consisted of a name, a place, a start date and a finish date.

Sometimes a subject would read a list of eight or ten ‘chapters’ with considerable ease; others might find the printing hazy or indistinct, and provide only partial information - and even then with considerable difficulty. Such points would provide the start position for future exploration.

Then we would consider each of the ‘lives’ in turn, taking the subject back to a point between the year limits indicated. Usually we started at a teenage date and progressively sampled points onward until the death year. This would give us a brief profile - a skeleton upon which the flesh would grow in future sessions. Extreme care was needed as we approached the time of impending death. Were we to take a subject through a death scene, the emotional trauma could be horrendous, and even with the most skilful desensitising procedure afterwards, subjects would more than likely bring back nasty mental and physical effects to their present everyday life. The usual procedure therefore was to take the person a safe distance beyond the known death date, and invite them to describe it as a memory, having first convinced them there would be no emotional difficulties. The work reported in this article took place largely between 1985 and 1988, and what we discuss here has to be regarded as a provisional report.

Don Brown

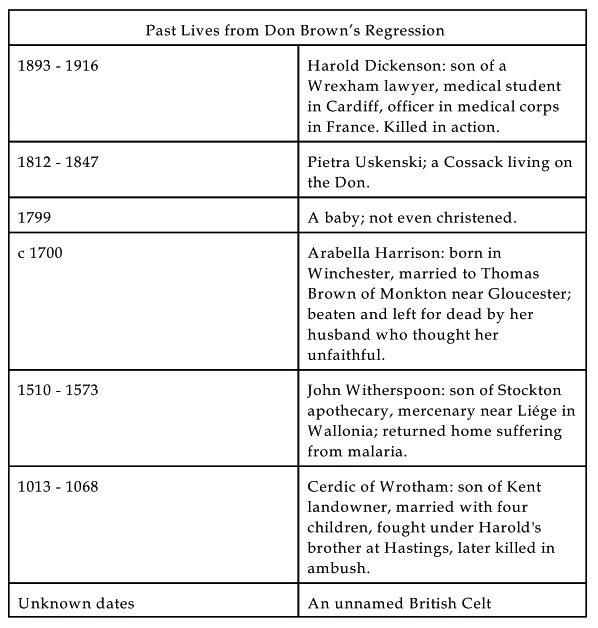

There were no initial indications that Don Brown (pseudonym) would ultimately be a star subject. Like several other members of the team it took some seven sessions over a period of several months before Don was trained to plumb the depths of deep trance. On the way there were very promising signs. When taken back to the age of 11, he amused us with a graphic and colourful account of selling programmes at a cricket match at Canterbury. Eventually he visited the magic library and took down the red leather-bound book embossed with his name in gold leaf, opened it, and read out some names, dates and places, which after further probing yielded us a list of past lives.

We decided to look at the most recent lives first, as these could be researched more easily. The nearest was Harold Dickenson, born in Wrexham, who in 1913 became a medical student at University College, Cardiff. He was a most promising character who joined the army before completing his degree course, and became a medical orderly at the Front in the Great War.

Harold had given us masses of useful information. Details of his regiment and company; names of superior officers; their uniforms and insignia; medical minutiae and operations carried out - tremendous stuff. And a little later out he went in a blaze of glory - over the top.

Historical Research

The very next day another of the team (a paramedic, as it happened), took all the information along to the Imperial War Museum, and after initial research very quickly found ... nothing of any evidential value whatsoever. What we had collected was a load of highly dramatic nonsensical fantasy. Nothing fitted whatever: all the military details were fictitious, the medical methods were wrong and none of the officers involved ever enjoyed a real existence. Almost every week one of our members visited St. Catherine’s House in Aldwych, the successor to Somerset House as the repository of British births, marriages and deaths since 1841, checking all the characters our subjects regularly provided us with.

Although we could dismiss Harold and hundreds of other past-life characters like him as being competely fictitious, there are nevertheless some curious points worth noting. As a student, Harold lived at Old Street which does not exist in Cardiff, but the area in which he resided did, and his regular walk to the College - past the Castle and other landmarks I knew were correct - even though Don had never been to Cardiff. In other subjects’ characters too, among a lot of dross and chaff, we encountered an occasional unexpected pearl.

The oldest existence encountered was a nameless Celt - and though there was much of interest, absolutely nothing was verifiable. As often happens, some characters are of the opposite sex. Such was Arabella Harrison around 1700. Observers were very amused when Don was asked the initial question ‘Who are you?’ ‘Arabella ...’ came the answer, which was followed quickly by ‘Arabella??’ as some part of Don’s observing self reacted in disbelief!

Cerdic

There was nothing immediately special about Cerdic. Apart from some initial difficulty over the pronunciation of his name (the nearest we could get was ‘Cherdik’, with ‘ch’ as in Welsh or the Scottish ‘loch’), we proceeded to build a profile by sampling a range of dates from teenage to death ... and beyond. As with all characters, our primary aim was to get them to tell us about their life and times, giving as many names, dates, and placenames as possible, yet without the operator asking leading questions.

Cerdic, and his father before him, were Anglo-Saxon thegns - minor nobility - at what is now Wrotham in Kent. He and his family lived off their land, farm or smallholding, defending it and the nearby coastline against sea raiders of several descriptions. With others he paid homage to the king and local earls by occasionally banding to defend the borders of the kingdom from the Welsh in the west and the Scots and Northumbrians to the north.

Cerdic and his family lived close to the land and learned to bear the vicissitudes of nature. Life could be hard, sometimes violent and bloody, but it had compensations too. In good years it was very good. Cerdic paid lip-service to the Christian faith, but secretly adhered to the ‘old ways’ inherited from the Norse tradition. The old social order was changing too; influences and pressures upon the English kingdom were from many directions. The Welsh and Northumbrians were a constant threat, and relations with Nordic neighbours were constantly blowing hot and cold. But there were now increasing rumbles from across the ‘little sea’, as royal relationships became strained with the Normans and Franks.

We first made contact with the Cerdic character in 1033 when he was 19, and proceeded to trace the milestones of his existence from this point onwards. We did so by progressing the character by a fixed number of years - usually 5 or 10 at a time. It was quite by accident that we chanced upon the year 1066, and unthinkingly I asked Cerdic where he was and what he was doing. My heart sank when he replied, ‘At a campfire, polishing my axe. Others are sharpening their swords - preparing for the battle.’

The Battle of Hastings

Clutching my head I grimaced painfully at the rest of the team. That was all we wanted! One of our great fears was that we might at some stage encounter Napoleon, Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, or lesser-known but prominent historical persons.

I scribbled a short note and passed it to one of my colleagues who then brought me a book on English history from my library. History has never been my strong point and I recalled nothing of the details surrounding the Battle of Hastings. Having quickly scanned the few pages that summarised this historic event, I addressed Cerdic again, confirming we were at the evening of 13 October 1066 - the night before it happened.

Cerdic and his fellow-fighters were assembled on a hilltop around a camp fire; the fires of William and his hosts could be seen in the distance. Cerdic outlined the events leading up to the confrontation. But an odd thing now happened. I asked non-leading questions, answers to which were in the history book open in front of me. And when Cerdic responded, the details were practically word for word according to the printed page, confirming little items like fighting under the Dragon banner of the king. It was almost as though Don was reading the book telepathically through my eyes. This sort of thing happened more than once and is discussed later.

Then I asked Cerdic something of a trick question - and there were no references to this in the history book. I invited him to look up and describe the night sky. He did so: ‘A bright, clear sky, stars, a quarter moon .....’

I asked him to look especially carefully for anything unusual. The popular modern impression, and one fostered by the concentration of events on the Bayeux Tapestry, suggests that Halley’s Comet was seen on the eve of the battle at Hastings. This was not so, of course, as we were relieved to hear Cerdic confirm.

‘Not now’, he said, ‘There was some time ago, a great fire in the sky - an omen - seven or eight months ago .... like a torch-head sweeping across the sky ...’ An omen it might have been though, for the English lost the battle the following day, basically because they broke ranks and were enticed into a trap. The then king, Harold, was killed by an arrow - not as popular account has it by hitting him in the eye, but according to Cerdic, ‘It was said that an arrow bounced off a shield into his face.’ At the end of the day Cerdic and the survivors fled the field and he passed the next and last two years of his life as an outlaw. His death and what happened afterwards fascinate too.

We returned to the battle on several occasions, and in fact devoted two whole sessions to this alone. We have an almost minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow, account, which is worth researching in more depth.

The Censor

In the life of Cerdic there was nothing our researchers could find material fault with: the historical facts are strikingly accurate. Some very minor discrepancies exist certainly, but nothing to invalidate the idea that something most unusual was going on. This is not yet to suggest that the Cerdic character is a ‘genuine’ past life. Detailed records of the period are virtually non-existent, and what is known to have happened is fairly accessible should anyone take the trouble to research it. But try as we did on many occasions, Cerdic was never caught out knowing more than he should!

He did however occasionally censor when he thought he was being tricked - he refused to name MacBeth as king of the Scots, when asked for his name (as one of several multiple-choice questions we often put). It probably sounded too obvious, even though it was in fact true.

Cerdic, the name of the legendary founder of Wessex, is thought to be of British origin. Our Cerdic married Sibel (or Cybele), wise woman or seer (Greek moon goddess), at a stone circle on the Welsh border in a ceremony that sounds like a Celtic sacred marriage of a king to his land. He could not run off his geneology back to some god or heroic ancestor (for example, the legendary Cerdic above), which is supposedly second nature to the Saxon/Germanic tribes that settled in Western Europe.

Our Cerdic gave the ‘classic’ Battle of Hastings scenario, untroubled by the new-fangled ideas voiced in recent years, and most of his ‘old ways’ festival celebrations are again more Celtic than Saxon (or Jute, from whom he claims descent). I would go further and say that I have personally encountered far more convincing characters in previous researches - intimate details of whose existences have been well and truly proven. But what makes Cerdic unique, and the events entirely without precedent in scientific research, is what happened next.

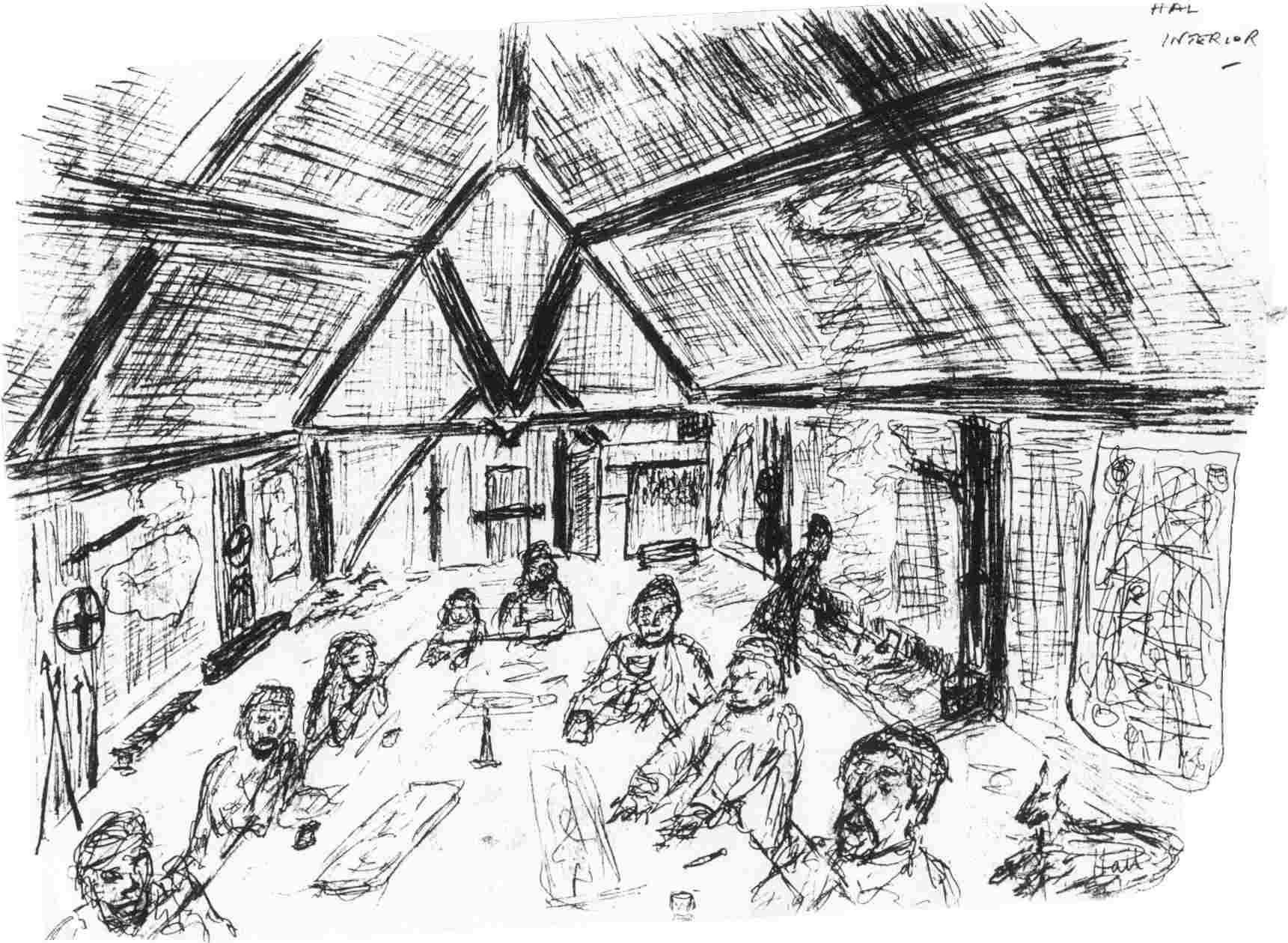

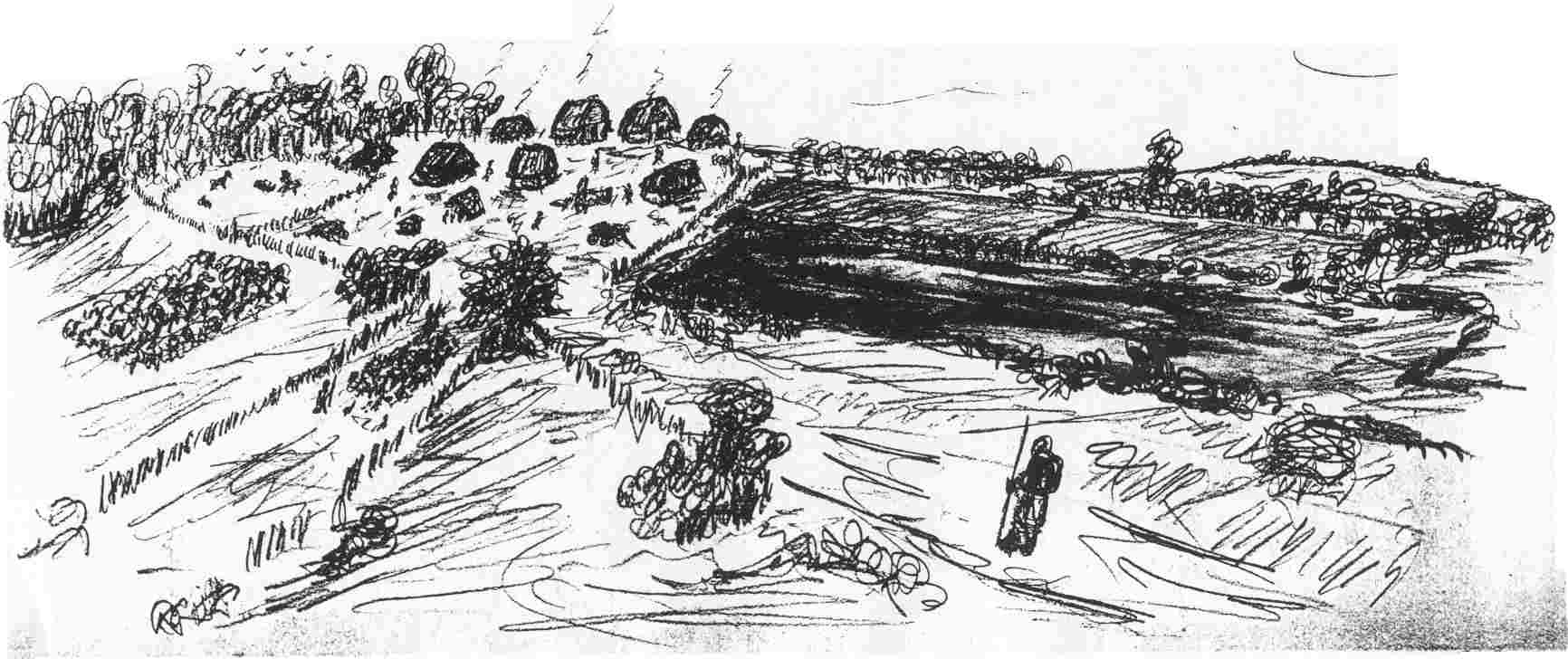

The Drawings

Before taking early retirement, Don Brown was a Senior Schools Inspector, and earlier in his career was a teacher and headmaster. His subject was geography, not history. Don was also a prominent local councillor. Consequently he spent a great deal of time in long and often boring committee meetings. As many people do, he doodled. Traditionally he did so with the geometric dot and angle pattern characterising a precise, logical mind.

The week in which the Cerdic character first appeared, the pattern of doodling changed, and changed dramatically. In a light reverie during an endless committee meeting the pencil lost its focus of attention and drifted gently across the page yielding a muslin of sensitive lines. Faces and places solidified from the mists of aons past. For some days Don wondered what was happening, then the realisation dawned. His pencil, when left to its own devices, was ‘automatically’ creating line drawings of the situations encountered with Cerdic.

The sketches now began to appear more and more quickly - at the rate of three or four a week. There was never any premeditation - the pencil just took over, as if it had a will and purpose of its own. The drawing had to be almost complete before Don recognised what it represented. And most of them were of considerable artistic merit - no mean achievement for someone who hitherto could not draw the proverbial two straight lines. Altogether, over a period of nine months nearly 150 drawings were obtained. Most related to Cerdic, but some referred to other characters from regression.

It seems as if the experience of deep trance hypnosis unlocked a latent artistic talent in Don, possibly something to compensate for the focused cut and thrust of his normal daily activity. These implications are discussed further later.

But another latent talent surfaced a little later too. In 1986 Don’s commitments had changed and he no longer managed to attend the regular Thursday evening hypnosis meetings. The pattern of automation then changed as well. In place of the pictures came words - but still seemingly of their own accord. The phrases Don’s pencil now scribbled were of a curiously archaic form. It was as though Cerdic wanted to tell his own story. That included his impressions of when ‘the voice called Hugh’ came to him.

As we witnessed on many occasions, it seemed not to matter where Don started the account - it was always consistent - just as if we were selecting a ‘tape’ or CD that could be played and replayed at will. The dates and times selected were always the correct ones, though the words were slightly different conversationally.

Don never made any notes of his experiences or the information gained during the hypnosis work - so once again what we are witnessing - at the very least - is one of the incredible attributes of human mind and memory. From Don we obtained a coherent, consistent, historically accurate past existence, details of which we could not trace from any records available to us. So far, they have given nothing to convince us of their reality, but this need not necessarily prove them otherwise.

Cerdic’s story was scribbled fast and in an unusual order. The middle portion concerned mainly with Cerdic followed on directly from the automatic drawings. Six months later Don was sitting on a hillside gazing out over the Weald of Kent, when suddenly he felt he ‘knew’ the story of Cerdic’s father Aeltan, and also that of his son Aelric. As with the Cerdic saga, the words came fast and furious. As Don pointed out, there was no time to stop and plot. The events took on a momentum of their own.

They retold at first hand what it may have been like in medieval England as a thegn in the Kingdom of Kent; living with Cerdic and his family, sharing their hopes and fears, seeing with his eyes, hearing with his ears, and working with his hands. Don entitled it ‘The Lost Land’. The later typescript was submitted to various publishers without success, and the book has yet to appear in print.

Discussion

Checks and Balances

One of the principal criticisms levelled at work where unusual mental phenomena are exposed is that the subject consciously prepared for the sessions by undertaking deliberate detailed research beforehand. It is theoretically possible Don may have done this, but from personal knowledge of his lifestyle and commitments, ‘leisure’ or ‘spare’ moments were extremely few.

Many people are impressed by the spontaneity of subjects’ responses. Answers to operators’ questions were never just ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Most often additional information came unprompted, amplifying, colouring, adding background and substance.

Assuming no historical research had taken place, the detailed knowledge of the events surrounding the Battle of Hastings was noteworthy. I have remarked previously about dates and their consistency. Perhaps a year after a particular hypnosis session, Don would be taken back to the same date. We would then be treated to the same sequence of events as on the previous occasion - though not word-perfect, of course, as the idea of a tape-recording might imply. And for dates worked regularly, the material is always as fresh as the first time encountered, untainted by Don or Cerdic having seen the outcome of certain events, even earlier in the same session.

Another critical point raised about the employment of modern dates is that medieval man would not have used them. Any specific day would be metered in relation to the major feasts, festivals, or events such as the lambing occurring six weeks after Yuletide. Agreed, but using the modern dating system does seem to act as an index or referencing system.

The reason for this is not hard to find. Many subjects report that under hypnosis, even in the deepest trance, however ‘possessed’ by an historical character they may be, there still remains a ‘small percentage’ of their ‘real’ selves that acts as observer and translator.

The idea of a translator is often cited as an explanation for another awkward observation. If the historical characters were ‘genuine’, we might expect Cerdic, for example, to talk to us in an Anglo-Saxon tongue. That he does not (for whatever reason) is attributed to this process of translation. We did of course ask Cerdic several times to speak in his own tongue without translation. Once, with enormous exertion, we were rewarded by a disjointed string of words that sounded remarkably like low German, but unfortunately the performance was not convincing overall.

Rather more so was a congruence I spotted while selecting some of Don’s drawings for a lecture presentation. One was drawn in February 1986 and the other some months later. The first relates to Cerdic’s home - the ‘ham’ (see picture below) - in prosperous times; the second was drawn to illustrate the havoc inflicted by ravaging Normans after the Great Battle. Apart from one hut slightly displaced, the two drawings are superimposable. And Don was quite unaware of this consciously until I pointed it out.

A most interesting comment was made by someone entirely unconnected with the project, and who at the time knew nothing of it. Don was at one of his interminable committee meetings one evening, and on account of its length, his sketch had approached the standard of a fully-detailed pencil picture. Suddenly, a colleague sitting beside him pointed at it and exclaimed, ‘I know that place - it is where the M20 curves near Wrotham!’

Another researcher, Roger Morgan, reported later he had checked the astronomical situation for the eve of the Battle of Hastings, and indeed a quarter moon should have been evident.

Wheat and Chaff

Researchers used to working in the paranormal field will know it is in the very nature of the material they deal with that there will never be evidence sufficiently complete or compelling to act as reasonable proof of a phenomenon for most critical but objective members of the scientific fraternity. In mediumistic utterences, some key facts may be provided - names, dates, places - but these will most often be dressed up with inconsequential trivia.

This was certainly our experience with several past-life characters, including to an extent Don’s Harold Dickenson. The best example in the present series of experiments was observed with Jennifer Harne, a character produced by Don’s wife Joan (pseudonym), who had also been trained to be a good deep-trance subject. In the early 1600s she had lived in Corsham, Wiltshire, and in the usual fashion had related information about life of the period. She had sketched a detailed plan of the village, with its houses, pubs, Guildhall and Saint Peter’s Church. Again, neither Joan nor Don had visited this area.

A team of about a dozen ASSAP members descended on unsuspecting Corsham one January Sunday entirely confident that nothing of value would be encountered in what we believed to be a relatively modern settlement. We were very surprised to find the historic inner town to be flask-shaped just as Joan had drawn, and it contained many of the same buildings, including the Guildhall, but placed differently. The Church was actually dedicated to Saint Bartholomew, but one of the two effigies carved prominently over the main entrance was undeniably Peter with his bunch of keys.

One of our number remarked casually that he would not be surprised, the Cosmic Joker being what it is, if we did not find a ‘Cross Keys’ public house along the road. We did encounter it, but a mile away and within minutes of closing time in the afternoon, but we had a few moments to document some most interesting examples of the Petrine symbolism it contained.

Another gem related by Joan was her naming Charles II as king in 1651, which was when he was proclaimed, although it took until 1660 for this to be universally accepted. We found this out later: at the time of asking, it was meant to be a trick question that initially we thought she had answered wrongly!

The ESP Dimension

While the existence of extrasensory perception has not been demonstrated to the satisfaction of critical scientists, libraries have been filled with anecdotal material which deserves our attention if for no reasons other than psychological ones. I have already referred to the possibility that some part of Don Brown’s personality was reading the information about the Battle of Hastings from the history book through my eyes. We decided to undertake what were originally intended to be fairly standard ESP tests, with the target person in deep hypnosis.

Clive Seymour volunteered to be the percipient, and had proudly given me a new set of Zener Cards to be used for the tests. A normal Zener pack contains 20 cards each of cross, circle, square, star and wavy lines. Clive’s pack included a recent development where individual symbols had distinctive colours, with the aim of aiding perception. Thanking Clive, and reminding him to report immediately the first image that appeared in his mind, he was hypnotised by another operator. Meanwhile I put the pack of cards decisively in my pocket where they remained for the duration of the tests.

Julie (pseudonym) had elected to be the agent as she had previous demonstrated a good rapport with Clive who was now lying on a low bed at the other end of the darkened room, and separated from Julie by several people. Taking care to avoid any clues or cues in Clive’s direction, I took an object from my pocket, handed it to Julie and told Clive to report the first ‘image’ that came into his mind.

After some seconds he seemed slightly perplexed and said, ‘Hugh, I know this is ridiculous, but the only thing I can see is one of your little blue model Mercedes cars’. He was actually entirely correct, as this is precisely what I had given Julie, but I just made sympathetic noises and invited him to have another try.

Once more, he failed to see any of the card symbols, but reported a green-handled screwdriver. Spot on again, and exhorting him to relax a little more deeply in the hope of being more successful, I handed Julie the third article - my wrist-watch.

Still apologising for his lack of card perception Clive described an expanding chain bracelet. I did not produce any further targets, and Clive’s responses then changed to standard Zener card symbols, but with chance expectation results. Afterwards, when I explained what I has done, his reaction was a mixture of elation and the unprintable.

Later we tried to develop the theme by having both agent and percipient hypnotised with their respective support teams in different rooms of the same flat, communication to be attempted at a pre-arranged time. Again some success, with a lot of uncommon material being reported simultaneously by both teams. However, as might be expected and could have been predicted, when we attempted to tighten the experimental conditions to the most rigorous extent .... no results of any evidential value were obtained. Nevertheless we feel it worth reporting these observations, anecdotal as they are, since they may be of benefit to other workers in future.

Regressing the Regressed

An intriguing experiment worthy of note attempted to find out whether past-life characters could themselves be regressed to past existences. Clive was already known to Cerdic as a benevolent character, and when I handed over control to Clive, Cerdic was quite willing to participate in ‘an experiment’.

Clive invited him to lie back, close his eyes, and relax ... ‘What, ... now?’ came the incredulous question, ‘But I’ll fall off my horse!’ Suppressing laughter at this unexpected spontaneity of context, and making an appropriate digital gesture to the Cosmic Joker, Clive invited Cerdic to dismount and lie down on the grass verge, and after hypnotic induction, we did reach the un-named Celt, whose information was very much in accord with that already on our records.

Range of Theories to Account for the Past Life Experience

Hoax

The possibility of deliberate hoax should never be neglected. Reasons for perpetration are many; from trying to hoodwink researchers, to seeking publicity or notoriety in reports, books, broadcasts and so on. However, subjects will need to have carried out their historical research very thoroughly indeed to evade the snares laid by experienced hypnotists and interrogators. They would also need to cultivate an unusual degree of spontaneity in responding to questions.

Fantasy

The dividing line between hoax and fantasy is extremely fine. The former involves more deliberate and conscious effort than the latter. Most hypnotists and all psychologists are aware of the imaginative role-playing ability of the subconscious mind, and nowhere is this more apparent than under hypnosis where suggestibility is heightened considerably.

The subject seems only too willing to please the hypnotist by providing an enormous wealth of detail. All too often the majority of the ‘evidence’ is the product of an enhanced fertile imagination, and it is regrettable that so much of this has been published in the past, quite uncritically, as proof of previous lives. As ever, a rigorous analysis of the material coupled with the most exhaustive historical research will point researchers in the right direction.

Cryptomnesia

Meaning literally ‘hidden memory’, this is the well-recognised ability for people to retain deep in the recesses of their memories the most mundane and irrelevant snippets of information taken in merely from a passing glance. Books read in childhood, newspapers once skimmed through, adverts ignored on TV; all these provide a reservoir of information for the imagination, in hypnosis, to dredge.

Facts, of which the waking personality would deny all knowledge, are assimilated into a plausible, coherent story. Many quite convincing published accounts of past lives have later been discredited by firm evidence that proved cryptomnesia was responsible. This is probably one of the greatest obstacles our research faces.

Multiple Personalities

Author and researcher Ian Wilson in ‘Mind out of Time?’ took a critical look at the whole field of regressive hypnosis, and concluded that the past-life characters are most likely to be members of a family of alternate personalities of the present-day subject. He does not imply that the people are in any way mentally disturbed, although in severe cases of psychosis the alternate personalities can be very distinct with apparently no knowledge of each other, as in the famous report of ‘The Three Faces of Eve’.

Ancestral Memories

Often put forward as a possible explanation, this model suggests that some memories may be handed down from generation to generation through the genetic code. There is no biological evidence for this: indeed the only information known to be transmitted by the genes in chromosomes is a specification for the synthesis of a range of proteins.

Having said this, instinctual information may be passed on in this fashion, but these are pretty basic behavioural patterns common to the species, compared with individual memories from one’s ancestors.

Some philosophers and psychologists deny that the entire range of memory has a physical seat within the body, in which case the ancestral memory option becomes a slightly stronger one, philosophically at least. If certain personality traits and characteristics are handed on in family lineage - by whatever mechanism - vestigial memory traces may also in some way be associated with the same process. However, a major objection to this theory is that the chain of succession may be broken by people dying childless.

Cosmic Data Bank or Akashic Record

Persistent in many religions and philosophies is the notion that everything one says, does, experiences or thinks about, is recorded somewhere. Akasha is a Sanskrit word - literally, a curtain - on which all this is recorded, and which a soul may consult to learn from past mistakes. Then there is the idea of the Big Black Book that will be opened on the Day of Judgement. In modern high-tech parlance such a concept might be expressed as a ‘cosmic databank’.

It is almost like suggesting that the total contents of our minds collected during a lifetime is transferred to this databank for long-term storage. Perhaps a certain combination of the personality elements of a sympathetically tuned hypnotist/subject team might provide a ‘key’ to certain ‘files’ within the storage system. The information provided would have been selected or filtered according to the - possibly unconscious - demands of the team. Chunks from different period of history could be similar or linked in some way, thus giving the impression of coming from past lives.

Spirit Entities

Another possibility not to be ignored is that in hypnosis we may be able to communicate with the surviving spirits of once mortal people, who can speak through the mind of the hypnotised subject, in much the same way as is claimed for Spiritualist mediums or sensitives.

In fact mediumistic trance and hypnotic trance are close members of the same family of phenomena, and more detailed comparison would yield intriguing information. During our research we were able to cause a subject to move from one state to the other by providing an appropriate stimulus.

Past Lives

Finally of course there are past lives themselves - the most familiar model of all. Here a ‘soul entity’, the ‘essence’ of a living being, is deemed to incarnate in a succession of bodies in turn, and it is memories of these past lives that are being accessed during the regressive hypnosis of the present-day subject.

In the case where the verbal material is of an exceptionally high quality, and intensive historical research has ruled out, in turn, hoaxing, fantasy and cryptomnesia, we are left with a few strong contenders which include the cosmic data bank, surviving spirits and genuine past lives. Perhaps they are all one and the same, or at least different facets of the same idea.

Mixed Models and Overlaps

The whole problem with models and theories is that no single one can account fully for observations, otherwise we would use stronger terms such as ‘explanations’ or ‘answers’. One profitable way to proceed, at least for the sake of discussion, is not to overlook the possibility that more than one may be invoked - at various times - to account for the material provided by a subject.

Indeed it is probably impossible - save perhaps at the deepest levels of hypnosis - to eliminate fantasy or cryptomnesia completely. But this should not prevent us from evaluating what we consider to be good material.

Taking another parallel with the study of mental mediumship, a sensitive may present some gems of veridical material, but this can be padded out with non-significant chaff. And there have been instances where ‘genuine’ phenomena have been helped along with a touch of fraud. We must be eternally on our guard to identify elements from several different models that may be mixed together in the same session. But we must also resist the temptation to pronounce that, just because there is some evidence of fantasy, the whole of the material must be dismissed as such.

An embarrassment to the past lives theory is where a subject reveals consistent characters whose lives overlap. In the present research we did not encounter this difficulty to any significant degree, but where it occurs, it could be accounted for by almost any combination of the remaining models.

The Fly-Paper Theory

In most areas of research where we start out with a variety of possible explanations, experience and experiment usually lead to a narrowing down of the field, and a preference emerges for this hypothesis or that. However, in four years of intensive work we failed to find overwhelming evidence for any of our starting models, and in fact had to add another major possibility.

While Wilson may be correct in believing that the past-life characters are alternate personalities of the present-day individual, there is another powerful variation on this theme. There is possibly within each of us a latent personality which is our unconscious desire and ambition for ourselves. This could lie completely dormant for most of a life-time, but like a fly-paper can draw to itself those facts and experiences gleaned from the vast reservoir of daily exposure, fleshing the skeleton which could pop out as a full character when - as in deep hypnosis - the circumstances are favourable.

A bus-conductor may see himself as a deep-sea explorer, a drudge-ridden housewife as Boadicea, or a company accountant as an engine driver; ambitions denied to each on account of background, upbringing or necessity.

In Don Brown’s case we noticed two factors to lend support to this hypothesis. First, four out of the six identifiable past-life characters were deeply involved in belligerent activities; Harry Dickenson in the Great War, John Witherspoon in Belgium, the Cossack Pyetr Uskenski, and of course Cerdic of Wrotham. Second, perhaps it is not coincidental that Don is also a seasoned fighter and campaigner, but these days with words and ideas rather than sword and hand-axe.

A spontaneous off-the-cuff remark made by Don during the debriefing period on the evening of Cerdic’s first appearance may be relevant. He said, ‘I can feel him wanting to come out.’

Acknowledgements

This paper is the result of an unusual team-effort of researchers. It is not possible to mention individually all the people who have contributed to the research over the years, but the following colleagues deserve special thanks: Harvey Appleby, Margaret Atkins, Geoff Barrass, Michael Bingas, Manfred Cassirer, John Dawes, Alf Fix, John Fraser, Paul Goodman, Val Hope, Sue Laws, Dee Marsh, John Merron, Annice Neville, Lesley Park, Jane and Ron Pepper, Tony Pritchett, Clive Seymour, Sue Seymour, Dave Smith, Tom Smith, Dave Thomas, and Caroline Wise. Paul Bew carried out much historical research and refined many of the experimental procedures used. His comments on this text have been appreciated, and these observations are incorporated in the discussion. Fellow hypnotists taught me a lot over the years, and I am grateful to David Christie-Murray, David Lowe, and Angus McHutcheon for comments and contributions to the experimental protocol.

Author :Hugh Pincott

Other ASSAP Articles

Unmatched Value, Unfinished Evolution: Why ASSAP Is Reviewing Membership for 2026

REVIEW: Even More…Ghost Stories by Candlelight at Shakespeare North Playhouse by Rob Gandy

Dark Secrets The Exhibition delights in darkness!

Previewing the Dark Secrets Exhibition!

ASSAP Announces Formation of Expert Advisory Panel

Exceptional Training Weekend - is available to book! Find out more!